This is a terrible book! As in, it is likely to strike terror in you if you are in any way cowardly. This book is not for the faint-hearted! If you are delicate, stay far away from this book.

This is a terrible book! As in, it is likely to strike terror in you if you are in any way cowardly. This book is not for the faint-hearted! If you are delicate, stay far away from this book.

This is probably the most horrific book I have ever read. Part of me did not want to continue – much less finish – reading it almost as soon as I embarked on the endeavour; such endeavour which soon became a dreaded task. Instead of getting better, it just kept getting worse and worse. The experience was akin to a “love-hate” relationship because, although I was appalled by the gory details and wished to flee far away from them, I knew I needed to exert fortitude to persevere, believing in the beneficial effects that would surely result from confronting the facts presented so graphically in this book.

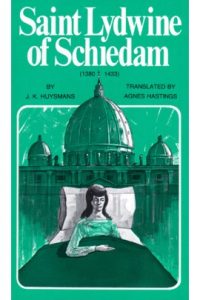

If you are accustomed to reading the specifics of what “Victim Souls” have endured, then you will probably not find this account particularly earth-shattering. However, having never read extensive and detailed biographies of such saints, this came as quite a shock to me. I knew how extreme the suffering of the saints could get… well... so I thought! What Saint Lydwine (also known as Saint Lydwina) endured, for many years, from around fifteen years of age until she died in her fifties, seems almost unimaginably excessive. I was wondering how commonly God calls upon people to suffer this much, and was relieved to read towards the end, in a section about the various “Victim Soul” saints, that, “…she [Saint Lydwine] was the greatest sufferer of whom we know.” I wish I had known before I started reading this that she held that distinction, and thus, could have been happily aware, in advance, that what was forthcoming is the worst it gets, as it were. Needless to say, the heroic sufferings of this amazing saint are in the category of “being for our edification and not for our imitation” – thankfully.

Regarding just the beginnings of her physical afflictions whilst she was only in her teens, we read, “Then all the quacks lost interest in her, and she gained at least for a time, the privilege of not being obliged to swallow useless and expensive remedies, but the trouble increased, and the pain became intolerable. She could get no ease, either lying, sitting, or standing. Not knowing what to try next, and being unable to remain a moment in the same position, she asked to be lifted from one bed to another, thinking thus to quiet her acute tortures; but these movements only exasperated the ill.

On the Vigil of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist her torments reached their culminating point. She sobbed on her bed in a state of terrible abandonment, and at last she could bear it no longer; her pain increased and tore her so that she threw herself from her couch and fell upon her father’s knees, who was seated weeping at her side. This fall broke the abscess, but instead of bursting outside, it broke within, and the pus poured from her mouth. These vomitings shook her from head to foot and filled the vessels so quickly that they hardly had time to empty them before even the largest was overflowing again.”

Abscesses, vomiting and pus aren't exactly my favourite things to even think about, much less to want to actually have!

Later on, as just one example from the melange of explicit descriptions of exceptional sufferings, we read, “Then she declared that her bed was too soft… then ordered them to lay a plank… on the damp floor of her room and to cover it with straw, which quickly became an abominable dung-heap, [it] was henceforth her sole bed. The task of moving her to it was, in spite of all their precautions, a terrible one. They had to bind her up in order that she should not break in pieces, and in raising her up they were forced to tear up the flesh which adhered to the sheet… At night she wept tears of blood which froze on her cheeks, and in the morning they had to detach these stalactites from her face, rough and blue with frost. As for the rest of her body, it was almost paralysed, and her feet were so stiff that they had to rub them and wrap them in warm clothes to reanimate them.”

There are, also, all sorts of freakish occurrences and supernatural phenomena going on, being frequent and common events surrounding her, amidst all this extraordinary suffering. It is truly incredible how much was crammed into one person’s lifetime.

Every page of this 252-page book is heavy matter. Don’t expect any hiatus once you start; as far as any respite, “abandon all hope ye who enter here.” Before even getting into the horrors of Saint Lydwine’s sufferings, we are immediately thrown into an intense and tumultuous scene, detailing the abysmal state of Europe during Saint Lydwine’s lifetime, from 1380 to 1433 AD. It was horrendous: political intrigues, revolts of the commoners followed by revolts of the nobles, wars (including that of Agincourt, immortalised by the play, Henry V), the conditions of France and England were particularly lamentable, the Black Death, additional plagues and famine, the list goes on.

The state of the Church, herself, was likewise dire. Interestingly, on page 18, it states: “The Holy Spirit... strayed about Europe, so that it was no longer possible to know what pastors to obey.” Then, more interestingly, on page 19: "She [the Church] had traitors in high places, she had horrible popes; but these Pontiffs of sin, these creatures so miserable, when they let themselves be led away by ambition, by hatred, by love of money, by all those passions which are the lure of the Devil, were found infallible directly the Enemy attacked dogma; the Holy Spirit, who was believed to be lost, returned to their assistance when it was a question of defending the teachings of Christ, and no Pope, however vile he may have been, failed in this.”

This deplorable state of affairs is explained initially, in sufficient detail, so we realise the necessity of having great saints, such as Saint Lydwine, being raised by God to expiate for the outrages committed against Him. One cannot help but compare the multitudinous, abominable and heinous crimes of our own times with those of the 1300s and 1400s – and ponder, wonder and shudder.

On a similar tone, the author states towards the end of the book:

"It must be added that at the present hour (1901), the wants of the Church are immense, and a wind of wickedness is blowing over the regions unsheltered by believers. There is a sort of slackness in devotion, a lack of energy."

He goes on, "One fact, at any rate, is undeniable; that in spite of the denials of those interested, the cult of Lucifer does exist; it leads the Freemasons, and silently influences the sinister jokers who govern the country, although you would not imagine, when they direct the assault against Christ and His Church, that they were the servants of a master in whose existence they do not believe! Clever as he is to get himself denied, the Demon does lead them.

The twentieth century therefore has begun as the preceding one terminated in France, with an infernal eruption; an open struggle between Lucifer and God."

What are we now - more than a century later with the world situation having grown exponentially worse - to make of all this? Perhaps these words of the author will inspire and motivate us:

"Would such a disaster have been avoided if there had been more monasteries of strict observance, more souls determined to inflict voluntary suffering on themselves and endure the chastisement which sin had made inevitable? We cannot reply directly to such a question; but it is possible to affirm that never till now has there been such need of a Lydwine; for such as she alone will be fit to appease the certain anger of the Judge, and to serve as a shelter against the cataclysms which are preparing!"

Imprimatured in 1922, originally published in 1923 and authored by J. K. Huysmans, this book is a collation of the three texts of Saint Lydwine’s life, one each by Thomas a Kempis, Jan Gerlac and Jan Brugman, all her contemporaries.

Dare you read it?